Ethiopia’s productive capacities are in a dire state and lagging behind other East African countries, according to the latest technical and statistical report by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), “Productive Capacities Development: Challenges and Opportunities — The Case of Ethiopia“.

Productive capacities are the productive resources, entrepreneurial capabilities, and production linkages that determine a country’s ability to produce goods and services — and ultimately, facilitate socioeconomic growth and development. Consequently, productive capacities are critically important for advancing structural transformation and economic diversification.

To measure productive capacities, UNCTAD has developed the Productive Capacities Index (PCI). The PCI is a composite index measuring productive capacities based on 42 indicators across eight categories: Natural Capital, Human Capital, Transport, Energy, ICT, Private Sector, Institutions, and Structural Change. The overall index score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating a higher level of productive capacities.

Productive Capacities in Ethiopia

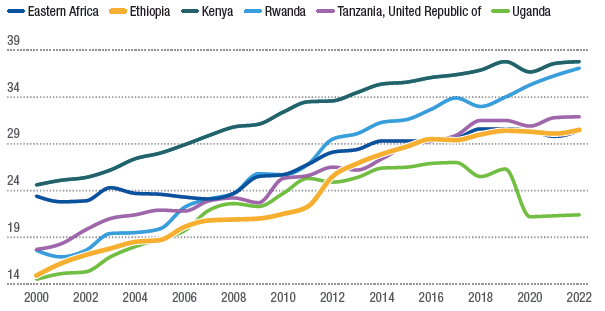

Ethiopia’s overall PCI score of 30.5 ranks 169th out of 194 countries and territories. Ethiopia continues to have low-levels of productive capacities relative to lower-middle income and low-income countries in East Africa, including Kenya (37.8), Rwanda (37.1), and Tanzania (31.9).

While Ethiopia has a higher PCI score than Uganda (21.4), its score remains lower than the median for Least Developed Countries (30.9) and the median for Landlocked Least Developed Countries (37.2).

Figure 1: Ethiopia’s Productive Capacity Index in Comparative Perspective

According to the study, Ethiopia’s low PCI score is a consequence of the country’s weak performance, gaps, and binding constraints in the following specific categories:

- Institutions

- Human capital development

- Low-levels of manufacturing value-added in GDP

- Dependence on the production and export of low-value agricultural commodities, with little or no technological sophistication

- Inadequate physical and natural capital

- Low-levels of ICT and innovation

- Non-conducive business environment for the development of the private sector

- Weak policy coherence and linkages

In sum, the report highlights that the country’s overall persistent deficit in productive capacities continues to be a barrier to increased economic competitiveness, inclusive growth, and productive socioeconomic transformation.

National Institutions

The institutions component of the PCI encompass critical elements of governance such as political stability, regulatory quality, rule of law, government effectiveness, control of corruption, and accountability.

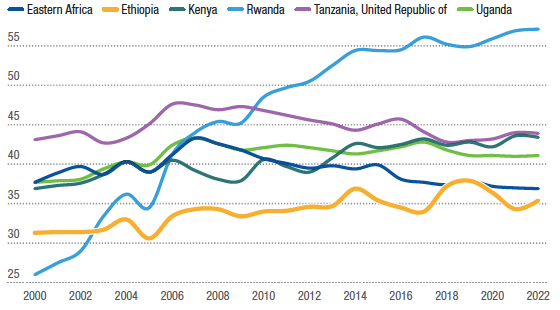

As illustrated in Figure 2, Ethiopia’s institutions PCI score of 35 remains well below Rwanda (57.1), Tanzania (43.9.), Kenya (43.4), Uganda (41.1), and the median for Eastern Africa (37).

Figure 2: Ethiopia’s Institutions (PCI)

According to the study, Ethiopia faces weak institutional architecture, weak regulatory quality, and a lack of independent institutions that are capable of accomplishing functions. Weak institutional capacity hinders the effective implementation and coordination of public policies and the ability to address complex socioeconomic, political, environmental challenges.

Furthermore, weak institutional capacity, ethnic profiling, and the absence of meritocracy makes policy formulation, implementation, and coordination difficult as well as undermines policy consistency and coherence leading to inefficient use of resources and increasingly corrupt practices.

To effectively implement development polices and build productive capacities to advance structural economic transformation and to achieve inclusive and sustainable development, Ethiopia needs to ensure functioning, independent, dynamic, and vibrant institutions.

Human Capital

The human capital component of the PCI captures the education, skills and health conditions possessed by a country’s population, and the overall research and development integration in society through the number of researchers and expenditure on research activities.

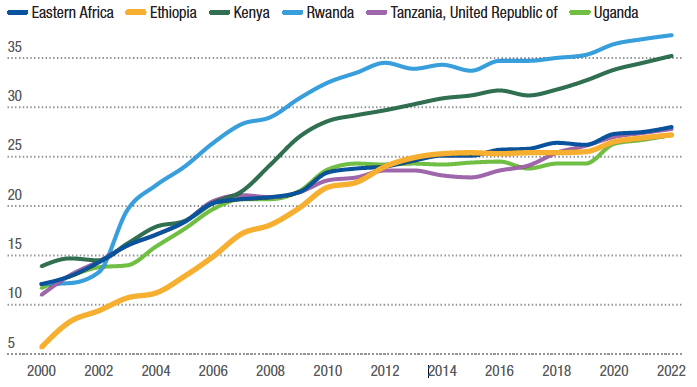

Ethiopia scores 27.2 on the human capital component of the PCI, which is lower than Rwanda (37.3), Kenya (35.2), Tanzania (27.8), and the media for Eastern Africa (28). While Ethiopia has made significant gains in human capital formation since 2000, largely driven by improved health outcomes, education outcomes remain inadequate.

Figure 3: Ethiopia’s Human Capital (PCI)

The study finds that the quality of education both at tertiary level and technical and vocational education and training (TVET) is low, and the learning achievements of most graduates are inadequate. For instance, the major challenges for TVET graduates transitioning to the labor market is a mismatch in skills development and a scarcity of formal jobs.

At the same time, in the labor market, firms report that skill gaps are adversely effecting competitiveness. Firms report three types of skill gaps: technical skills related to work, work ethics, and literacy (ability to read with understanding and write at a level relevant to a job).

Addressing the skills gap will be crucial for the Ethiopian economy to improve competitiveness, export performance, job creation, and incomes. This requires aligning education and training policies with the needs of the labor market through, for example, fostering effective linkages between industry, universities, and research institutes.

Private Sector

The private sector component of the PCI encompasses the ease of cross-border trade, including the time and monetary costs to export and import, support to businesses in terms of domestic credit, velocity of contract enforcement, and the time required to start a business.

Ethiopia’s private sector development is still at a nascent stage. Despite progress in socioeconomic outcomes through state-led investments, success in igniting private sector growth has been very limited.

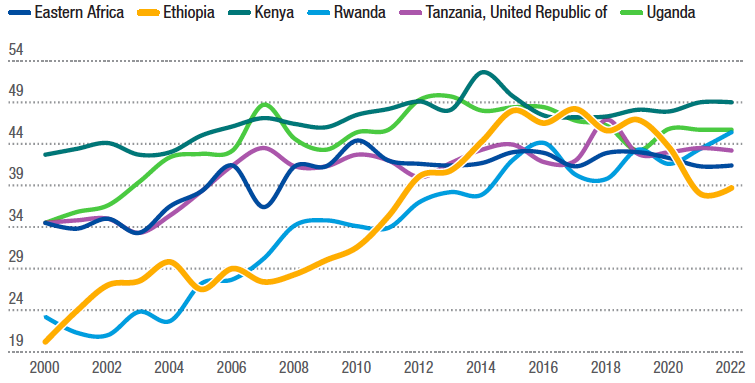

Until 2009, Ethiopia’s private sector PCI score was higher than comparator countries. However, due to a decline between 2006-12, as well as a stagnation since then, Ethiopia’s current score of 37.7 is lower than that of Kenya (44.2), Rwanda (40.3), Tanzania (39.8), and the median for Eastern Africa (37.8).

Figure 4: Ethiopia’s Private Sector (PCI)

In recent years, some measures have been introduced to encourage the participation of the private sector, including trade and financial sector liberalization and the privatization of state-owned enterprises; nevertheless, “the country lacks a comprehensive and coherent private sector development strategy that promotes the domestic private sector.”

In this regard, the study identifies several binding constraints undermining the private sector such as an unfavorable business environment, inadequate infrastructure services, barriers to regional trade, procedural obstacles and non-tariff barriers, limited access to finance, and political instability and ethnic-biased policies.

Structural Change

Structural change refers to the ability of a country to undergo effective structural economic transformation and the propensity a country exhibits towards that process. This is captured by the sophistication and variety of exports, the intensity of fixed capital, and the weight of industry and services in total GDP.

According to the study, Ethiopia has undergone limited structural change and exhibits the “wrong” type of structural change, including a precipitously low-level of manufacturing value-added in GDP. The country has also experienced a transformation to low-skilled services sectors, which has made little impact on poverty reduction.

As captured by Figure 5, Ethiopia’s score in the structural change component of the PCI grew rapidly between 2000 to 2015 — increasing from 20.2 to 48 — then stagnated until 2019, at 46.9, before it declined to 38.7 in 2022.

Ethiopia’s score of 38.7 is the lowest in the group — outperformed by Kenya (49), Uganda (45.7), Rwanda (45.4), Tanzania (43.3), as well as the median for Eastern Africa (41.4).

Figure 5: Ethiopia’s Structural Change (PCI)

Fundamentally, Ethiopia’s persistently low-level of structural transformation reflects the lack of diversification into manufacturing and other higher value-added activities, which constrain competitiveness and the development of productive capacities.

Furthermore, the country continues to experience a movement of labor from low productivity activities to other low productivity activities (e.g., trade related services), indicative of a structural burden which hinders productivity, economic growth, and structural transformation.

Policy Recommendations

The UNCTAD study identifies critically important policy recommendations to ensure the building of economy-wide productive capacities in order to advance structural economic transformation, economic diversification, and sustainable development in Ethiopia. Specifically, the recommendations are to:

- Prioritize productive capacities for structural transformation

- Ensure political stability

- Adopt a holistic approach

- Enhance industrialization and sectoral development, and build linkages

- Strengthen human capital development and address the mismatch in skills’ supply

- Create new jobs, particularly for youth

- Strengthen institutions, improve policies, and coordination

- Address macroeconomic imbalances

- Leverage domestic and foreign direct investment

- Intensify support for private sector development and foster entrepreneurship

- Expand infrastructure and enhance connectivity, while facilitating green transformation

- Improve access to electricity

- Invest in ICT and innovation

- Improve financing for development

The extent to which Ethiopian authorities commit to and implement these recommendations will directly impact Ethiopia’s productive capacities and future socioeconomic trajectory.

Notwithstanding, in recent years, the policy agenda, political will, and institutional capacity to strengthen productive capacities and facilitate structural economic transformation has been severely curtailed.