Authors: Mussie Delelegn Arega*, Mussie Mindaye Hailesillassie**, Tadele Ferede Agaje***, and Yetsedaw Emagne Bekele****1

Introduction

Ethiopia has embarked on major economic reform programmes since the 1990s, which have intensified and deepened over recent years. There are concerns about whether such reforms will address deep-rooted structural constraints to the country’s development. The Bretton Woods Institutions that sponsored the reforms have been issuing their respective assessments of progress, challenges, and prospects for the country’s economy. Fracturing multilateralism, declining official development assistance (ODA), and growing trade protectionism in developed countries are expected to worsen global trade and economic outlook — dampening the trade and growth prospects of weak and vulnerable economies such as Ethiopia’s.

Against this backdrop, we undertook a comprehensive study on the impact of recent United States (U.S.) tariffs on Ethiopia’s export competitiveness, economic growth, and development prospects. The study, which is currently under peer review for publication, titled “Initial assessment of the likely effects of recent U.S. tariff measures on Ethiopian exports”, employs a combination of statistical and econometric models, and provides incisive analysis with policy conclusions and recommendations. This overview is, therefore, based on the broader policy significance of the study in the field of international trade, including bilateral trade between Ethiopia and the U.S.

Our empirical and econometric study seeks to assess the likely effects of U.S. tariffs, identify the most at risk industries, and recommend strategic responses to mitigate adverse effects and protect Ethiopia’s trade interests. It also offers policy recommendations for Ethiopia on how to best limit or reduce the ramifications of new U.S. tariffs on the country’s export competitiveness.

Research Background & Overview

Historical and empirical studies show that developing economies, particularly those in Asia2 and Latin America3 have benefited from integration into the global economy through export growth and diversification. In Africa,4 with the exception of a few countries, the success rate has not been that encouraging. While Africa’s merchandise exports remain dominated by low-value, unprocessed commodities — mainly from extractive sectors — many successful economies in other developing regions have shifted toward exporting manufactured goods and knowledge — and technology — intensive services.

The relationship between exports, economic growth, and poverty differs across countries, influenced by the nature of exported goods, level of value addition, and the extent of integration into global markets.5 In most cases, high-value exports generate decent employment and income through their impact on learning and technological catch-up, as well as by fostering competitive firms and industries. In other cases, exports finance imports and improve investments in infrastructure or imported machinery, technology, and capital goods. In all successful cases, a favorable global trading environment based on multilateral trade rules facilitated beneficial integration of developing countries into the multilateral trading system and the global economy.

Although Ethiopia has been undertaking externally prescribed policy reforms, particularly in recent years, its exports are predominantly agricultural and, given its least developed country status, the country has been benefiting from duty-free and quota-free market access offers, including from the U.S. African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), until January 2022. Ethiopia was removed from AGOA due to alleged human rights violations committed by the Ethiopian Government during the war in Northern Ethiopia.6

Beyond the lack of export diversification and limited transformation on its export structures, as with many structurally vulnerable economies, Ethiopia suffers from weak productive capacities, low-level of structural economic transformation, persistent macroeconomic instability, and little socioeconomic gains from its wide-ranging reform programmes, at least in the short run.

In this regard, the above cited study reveals that Ethiopia’s improved growth in export earnings in recent years, has been driven primarily by rising global prices, with only marginal increases in export volumes. The study also underlines that the country’s growth-dampening impediments and structural challenges persist, namely, limited export diversification, a low and declining export-to-GDP ratio, and heavy dependence on a few agricultural commodities such as coffee, oilseeds, and gold. For example, just ten products account for over 92% of Ethiopia’s exports, with Asia and Europe as the dominant markets.

Amid reforms under the “Home Grown Economic Reform Agenda”, the country’s export sector remains vulnerable to external shocks. The study particularly reveals that although the U.S. accounts for only 8% of Ethiopia’s exports, a significant recent shock in global trade came with the U.S.’ imposition of new tariffs, in early 2025, on imports from 185 countries, including Ethiopia. Specifically, Ethiopian exports now face an average tariff of 10%. If threats of an additional 10% tariff materialize, due to Ethiopia’s BRICS membership, the adverse impacts on Ethiopia’s exports would be colossal. These moves follow Ethiopia’s suspension from the AGOA in 2022, compounding further the structural challenges faced by the country’s export sector.

Although the average Most Favored Nation (MFN) tariffs for agricultural exports of Ethiopia are modest, the imposition of a 10% U.S. tariff on the country’s exports would adversely affect its export competitiveness. It would also depress demand due to higher prices, particularly harming smaller exporters. The study also concluded that, while Ethiopia’s import from the U.S. constitutes, primarily aircraft and related components, these are largely exempt from tariffs and other duties.

Key Findings

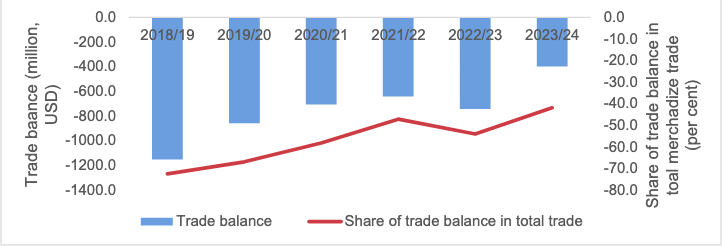

While the key rationale behind U.S. tariffs is the claim that such measures aim to reduce trade deficits, in the case of Ethiopia, the U.S. has consistently maintained a trade surplus (Figure 1). While Ethiopia’s exports to the U.S. have grown at an average annual rate of 4.8%, the U.S. share in Ethiopia’s total exports has been on a precipitous decline over the years. This finding could serve as the basis for engaging in evidence-based negotiations and advocating for a review of the U.S. tariff policy toward Ethiopia.

Figure 1: Ethiopia’s Trade Balance with the U.S.

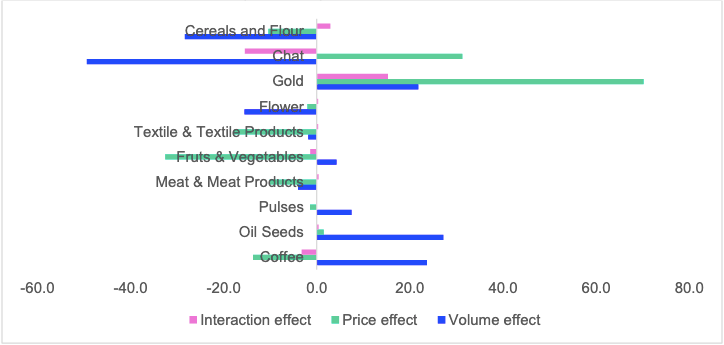

As mentioned above, and illustrated in Figure 2, the research finds that the recent uptick in Ethiopia’s export earnings are largely driven by rising global prices and only a marginal increase in export volumes. Moreover, with per capita exports of just $30 in 2023, Ethiopia ranked 204th globally out of 209 countries for which data was available. This means that Ethiopia is not a large trading nation even by the standards of African countries. Rather, it relies heavily on imports including from the U.S. In addition, Ethiopia’s export competitiveness will be at greater risk with the fluctuation of global commodity prices — recent improvement of which has been central to the country’s improved export earnings.

Figure 2: Decomposition of Export Growth by Volume and Price Effects for Major Exports, 2022/23-2023/24 (%)

At the sectoral level, the study finds that Ethiopia would likely gain a relative competitive edge in textiles and garments exports due to more favorable tariff treatment in comparison with large global exporters such as China and Vietnam, despite its small market share. Meanwhile, U.S. imports of textiles and garments may decline overall, especially from Asian suppliers, while Ethiopia’s textile imports could rise, possibly reflecting possible trade diversion from Asian exporters or increased domestic demand for Ethiopia’s textile exports due to price differential.

In 2024, Ethiopia’s exports of textiles and garments to the U.S. accounted for a modest yet notable share, roughly 1.5% of Ethiopia’s total exports. It is important to note that regional competition and evolving tariff regimes may influence the scale and trajectory of these exports, particularly if Asian economies slash the cost of production, driving down the consumer price for textiles and garments.

In addition, according to the study, following new U.S. tariffs, major leather exporters like China, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Italy saw declines, while Ethiopia’s exports rose by 3.2%, likely due to minimal tariff exposure and untapped capacity. This presents a strategic opportunity for Ethiopia to expand in the U.S. market, provided that the country improves its supply capacity and export cost competitiveness.

However, exports of leather products to the U.S. remained minimal, accounting for just 0.10% of Ethiopia’s total exports in 2024. On the other hand, Ethiopia’s oilseed exports to the U.S., which made up of just 0.3% of total exports, declined slightly by 0.1%, reflecting reduced global demand and the non-essential nature of oilseeds with U.S. import volumes and prices dropped across the board, especially for value-added oilseed products.

Under recent U.S. tariff changes, at the time of writing, Ethiopia faces a 10% tariff — similar to Brazil and Colombia — but lower than those imposed on key competitors such as Vietnam (46%), Indonesia (32%), Switzerland (31%), and the EU (20%). While this does not give Ethiopia a unique advantage, it allows the country to remain competitive through improving product quality and expanding value-added exports, such as roasted coffee as well as enhanced supply capability. In 2024, the U.S. accounted for approximately 4.7% of Ethiopia’s exports of roasted and unroasted coffee. While this represents a notable share of Ethiopia’s overall coffee exports, it remains modest compared to other major markets.

Likewise, on cut flowers, the U.S. is the largest global importer, with Ethiopia accounting for just 0.4% of these imports in 2024. The newly imposed tariff applies uniformly to Ethiopia and key competitors, offering no immediate comparative advantage to the country. This means that, overall, the new tariffs raise import prices, dampen U.S. demand, and place smaller exporters like Ethiopia at a disadvantage, contributing to the decline in export volumes.

Conclusions & Implications

The radical changes in U.S. trade policy from supporting the trade and development endeavors of poor countries such as Ethiopia toward “transactional” trade and investment relations, undoubtedly, will have significant ramifications on bilateral, regional and multilateral trade, and investment relations. Given the ongoing global rivalry for influence in Africa, transaction-based relations may undermine the U.S.’s strategic engagements, influence, and position in Africa.

At the country level, the recent imposition of U.S. tariffs poses notable challenges to Ethiopia’s export performance, particularly for sectors such as oilseeds and cut flowers. However, it also presents strategic openings in industries such as leather and textiles, where modest gains are possible due to relatively favorable tariff treatment, if Ethiopia can address its age-old structural rigidities in production and export competitiveness. Given that Ethiopia’s recent export growth has been largely price-driven rather than volume-based, the country needs to prioritize structural reforms that enhance competitiveness and resilience.

To enhance Ethiopia’s competitiveness in a shifting global trade landscape, the following actions are recommended:

- Proactively, engage in evidence-based trade negotiations with the U.S., advocating for a review of current tariff measures on Ethiopian exports. These negotiations should be supported by clear evidence, including the persistent U.S. trade surplus with Ethiopia and the fact that key U.S. exports — such as aviation products — enter Ethiopia duty-free.

- Ethiopia needs to foster a dynamic and competitive domestic private sector by enhancing private sector capabilities, improving governance and business regulations, facilitating access to finance, and improving the ease of doing business.

- Leverage tariff differentials to attract investment in labor-intensive manufacturing sectors, positioning Ethiopia as a cost-effective alternative in global supply chains.

- Pursue the reinstatement of preferential trade access, particularly through rejoining AGOA, to regain duty-free market entry and boost export competitiveness.

- Strengthen productive capacities and promote structural transformation by increasing the value-addition and technological sophistication of exports in sectors where Ethiopia holds a dynamic comparative advantage.

- Capitalize on regional and global opportunities, including the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), China’s Duty-Free, Quota-Free (DFQF) market access initiative for African exports, and the EU’s Everything But Arms (EBA) initiative. However, meeting the increasing non-tariff barriers of the EU is becoming costly and cumbersome for developing countries such as Ethiopia. EU, Ethiopia’s largest export market for coffee (45% in 2023), recently introduced a Deforestation Free Regulation7-EUDR- which will adversely effect coffee exports particularly from Africa.

By implementing these measures, Ethiopia can reduce its trade vulnerability, diversify its export base, and position itself as a resilient and competitive player in global markets, supporting inclusive and sustainable economic growth. Otherwise, a small decline in international prices including in sectors that Ethiopia has comparative advantages may cause greater vulnerability to the country’s socioeconomic progress.

_______________________________________________________________________________

References

- Authors are listed in alphabetical order. The opinions and views expressed in this study are the authors’ own and do not reflect or represent the official views of institutions or organizations they are affiliated with.

*Mussie Delelegn Arega, Head, Productive Capacities & Sustainable Development Branch, Division for Africa, LDCs and Special Programmes (ALDC). His contribution is in full consideration of ST/AI/2000/13 section 2, and it is in his personal capacity.

**Mussie Mindaye Hailesillassie, Policy Advisor, GIZ, Ethiopia (email: hailesilassiemussie@gmail.com).

***Tadele Ferede Agaje, Associate Professor of Economics, Department of Economics, Addis Ababa University (email: Tadele.Ferede@aau.edu.et).

****Yetsedaw Emagne Bekele, Consultant, World Bank, Ethiopia (email: emagneyetsea15@gmail.com). ↩︎ - Includes vibrant and dynamic trading nations such as China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, the Republic of Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, and Vietnam. ↩︎

- The list includes Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, and Uruguay. ↩︎

- Mauritius, Morocco, South Africa, and to some extent Tunisia. ↩︎

- World Bank Group and World Trade Organization (2015). The Role of Trade in Ending Poverty. World Trade Organization: Geneva. ↩︎

- https://agoa.info/news/article/15897-ethiopia-pushes-to-keep-agoa-access-amid-u-s-rights-concerns.html. ↩︎

- The EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) aims to minimize the EU’s contribution to global deforestation and forest degradation by ensuring that certain products (cattle, cocoa, coffee, palm oil, rubber, soy, and wood, as well as some derived products), placed on the EU market or exported from it are deforestation-free if proven that they are produced on deforested lands. ↩︎