Against the backdrop of tattered global development partnerships and constrained multilateralism, the Third United Nations Conference on LLDCs (UNLLDC-III) will be held from 5 to 8 August 2025 in Awaza, Turkmenistan. There, the international community is expected to renew its longstanding commitments to seek solutions to relieve the key binding constraints to landlocked developing countries (LLDCs) and enable their beneficial integration into the global economy.

This article provides policy insights and recommendations on fostering LLDCs’ resilience to unforeseen shocks, risks, and economic uncertainties. This can be done by reorienting domestic policies and international partnerships towards the building of productive capacities1 and facilitating LLDCs’ integration into higher value-added supply and regional and global value chains (RVCs and GVCs)2.

The core argument is that while LLDCs face many challenges (emanating from being landlocked), the root causes of their underdevelopment lie in their weak productive capacities. Experience shows that it is practically impossible for countries to pursue industrialization, foster sustainable structural transformation, and engage in supply and value chains without developing their productive capacities.

An important lesson drawn from two landlocked developed economies (Austria and Switzerland) is that being landlocked is a challenge, but it is not insurmountable. The unprecedented high levels of production sophistication, structural economic transformation, innovation and global competitiveness observed in the two countries can provide hope and inspiration for LLDCs.

These are grounded on a clear identification of comparative advantages and mapping and sequencing intervention strategies to enhance capital accumulation and build productive capacities. The key drivers in these processes are increased investments in research and development, building institutions, and human capital formation. These are complemented by fostering technological capabilities and intensifying strategic integration into high-end RVCs and GVCs. Today, the two countries are known to produce high knowledge, skills and technology-intensive goods and services for domestic consumption and for exports to regional and global markets.

Why Do Productive Capacities Matter for LLDCs?

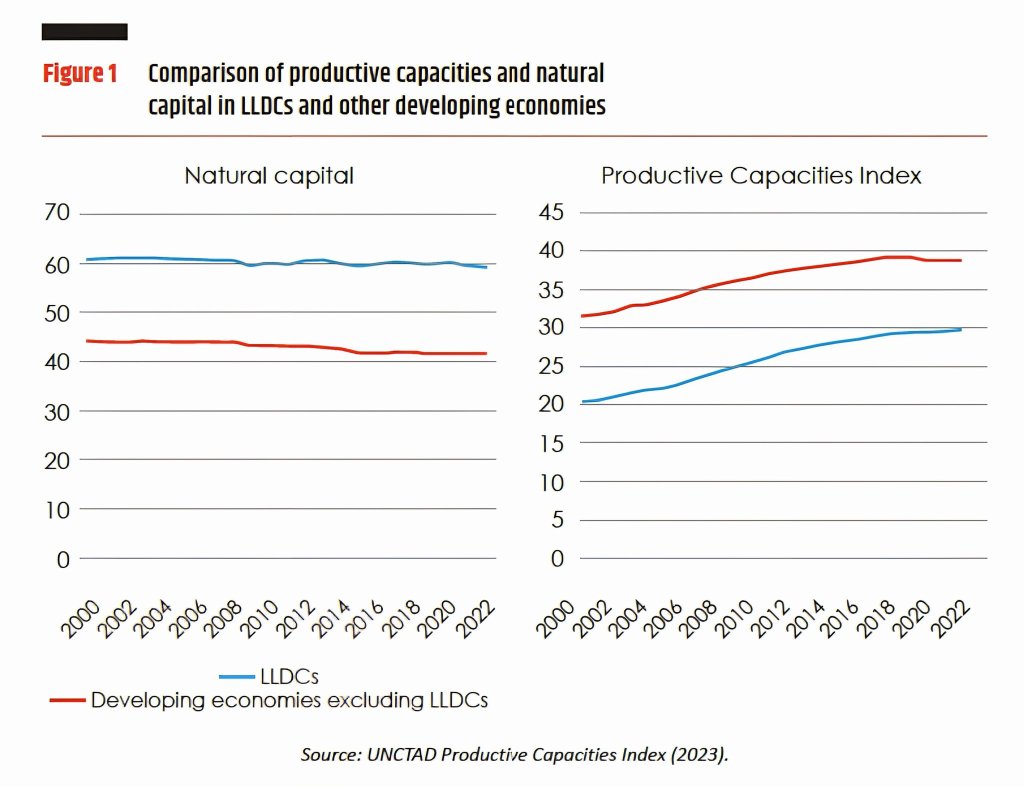

Currently, there are 32 developing countries3 without direct access to the sea, of which 16 are in Africa, 14 are in Asia and Central Europe, and 2 are in Latin America. While these countries hold immense natural capital (including agricultural land, water, forest, oil and gas, and mineral resources), they suffer from a combination of geographical challenges, weak productive capacities, and poor integration into supply chains, RVCs, and GVCs.

Their structural challenges are further compounded by poor infrastructure, undeveloped trade logistics, and problems related to transport, electricity, and information and communication technology (ICT) connectivity, which result in high production and trade costs. In addition, their production efficiency and cost-effectiveness of their exports largely depend on and are influenced by their political relations with transit neighbors.

Most LLDCs are commodity dependent. Their productive structures register low levels of economic complexity, with exports containing little to no value-added and highly concentrated in a few destination markets. Consequently, primary commodities account for more than half of the exports of 27 of the 32 LLDCs.4 Most of them are also producers and exporters of precious stones and metals, as well as critical minerals vital for the energy transition.

Some have vast agricultural lands, forests, and freshwater resources, but are regarded as food-insecure or net-food-importing. Value-addition and retention of natural capital, as well as fostering linkages with the rest of the economy, remain among the most pervasive problems facing LLDCs. This heightens their socioeconomic vulnerability, resulting in their marginalization in the global economy.

In short, fostering productive capacities is key to addressing the main binding constraints to LLDCs’ development and enabling them to harness their comparative advantages by kick-starting the process of structural economic transformation.5 This is the sine qua non to achieving long-term and inclusive growth and development, breaking the low- and middle-income traps and reducing aid dependency, while building socioeconomic resilience.

Supply Chains Versus Value Chains

From a trade and development perspective, the theoretical distinction between ‘supply chains’ and ‘value chains’ is immaterial for LLDCs and, therefore, it is intentionally ignored in this article. Instead, the focus is on overcoming challenges and exploring opportunities to foster productive capacities, develop sustainable domestic supply capabilities, and join high-end value chains in key sectors linked to their comparative advantages. That is, without developing productive capacities and domestic supply chains, it will be difficult for LLDCs to beneficially integrate into RVCs and GVCs. Nor will it be easy to break away from a low-level equilibrium trap (characterized by low productive capacities, low income, low employment, and little or no development outcomes). Transitioning from the supply of poor-quality, or low-value, high-volume raw materials towards strategically joining RVCs and GVCs depends on how quickly LLDCs develop productive capacities and foster export diversification, value addition, and overall structural economic transformation.

Supply Chains Without the Requisite Productive Capacities will not be Sustainable

For LLDCs, effectively addressing their development challenges means reducing their economic dependence on commodities and moving away from natural resources-driven activities to more sophisticated knowledge and technology-intensive economic activities, including service.6 However, this cannot be realized without fostering productive capacities and kick-starting the process of structural economic transformation, which are key to fostering reliable and predictable domestic supply chains and tapping opportunities provided by RVCs and GVCs, particularly in agriculture and critical minerals.

This calls for a new development paradigm anchored in re-calibrating, utilizing, and maintaining existing productive capacities, as well as developing new capabilities.7 For instance, effectively harnessing and value-adding to the natural capital—one of the eight categories of the Productive Capacities Index (PCI)8—calls for carefully sequenced and mutually supportive policies, as well as educated and skilled human capital, a dynamic private sector, affordable energy (electricity), technology-driven infrastructure connectivity, and capable institutions to maximize development outcomes.

LLDCs rich in extractive resources should orient their micro and macroeconomic policies, sectoral strategies, and human resources development programmes towards sustainably harnessing such resources. The growing demand for critical minerals particularly offers new opportunities to transform their natural resources at the moment of upstream production and facilitate their insertion into value chains, as opposed to the current practice of supplying raw materials to low-end segments of value chains.

Fostering vibrant and dynamic institutions that provide regulatory and legal frameworks is key to capturing rents from natural resources in socioeconomic development, while effectively dealing with rent-seeking behaviors such as patronage and corruption, which often contribute to political instability and conflicts.9 Likewise, LLDCs rich in agricultural resources must invest in enhancing productivity, building rural infrastructure, and fostering domestic linkages between agriculture and the industrial and services sectors.

This will require LLDCs to move away from short-term, project-based, and fragmented interventions towards long-term, coordinated, and holistic development programmes. Such approaches are key to recalibrating productive capacities along the eight categories captured by the PCI. These are more persuasive today than ever before, given the fast-changing global development partnerships and difficult international trade and investment environments, riddled with heightened risks, unpredictability, and uncertainty.

It is essential to leverage productive capacities to ensure that they contribute to the development of domestic supply chains and help LLDCs to harness opportunities that RVCs and GVCs offer. To that end, LLDCs must realign their micro and macroeconomic as well as infrastructural and sectoral policies with developing domestic supply chains. This is vital to successfully joining a web of RVCs and GVCs and ensuring the timely delivery of raw materials and other intermediate inputs to manufacturing enterprises. However, despite immense natural capital, the productive capacities of LLDCs are much lower than those of other developing countries, as can be observed in Figure 1.

Integrating into complex supply and value chains where resources, suppliers, producers, consumers, and markets interact in step-by-step processes is even more challenging for LLDCs. In such complex processes where policies, geography, technologies, and institutions are aligned to drive interactions, effective participation requires developing economy-wide productive capacities, including a dynamic private sector, skilled labour force, functioning institutions, and modern rules and regulations.

LLDCs have long been constrained by the theory of comparative advantages, which argues that resource-rich countries should focus on and specialize in supplying raw materials where their comparative advantages lie. This implies leaving the value addition to countries that are technologically well-off and have already developed their productive capacities to extract, maximize, and retain a disproportionately large share of value.

Such theoretical arguments have further entrenched age-old exploitative relationships, ignoring the dynamic potential of comparative advantages, which can be promoted and harnessed in upstream production and supply echelons, as well as in downstream production and consumption chains.

Challenges and Opportunities

Global competition has transformed how products are made, transported, value-added, and eventually consumed. At the same time, both supply and value chains are susceptible to unforeseen shocks, be they financial, economic, technological, political, health-related, or environmental.

There are opportunities for natural resources-rich developing countries to become manufacturing hubs and suppliers of technologically sophisticated goods and services, due largely to the low-cost advantages they possess for raw materials and labour. This is further accelerated by the movement of capital through FDI and high input and production costs in developed and emerging economies. These developments have opened new avenues for production transformation for firms and nations to maximize their competitive and comparative advantages.

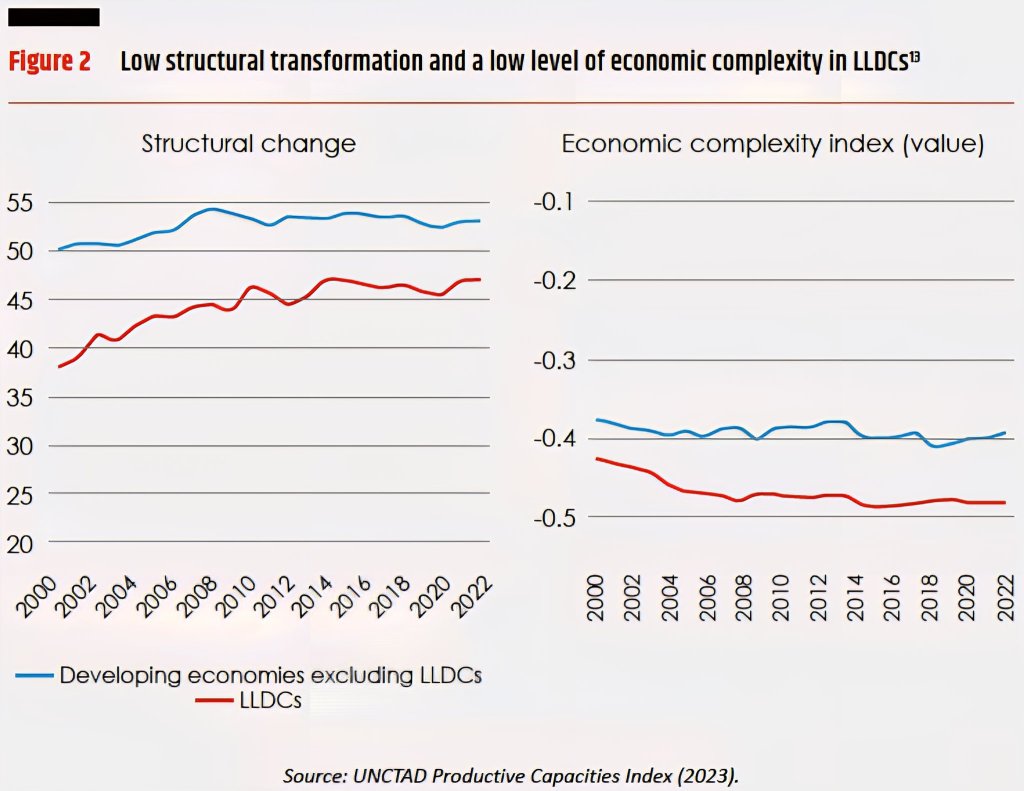

However, LLDCs perform poorly not only on the PCI, but also in structural economic transformation. United Nations Trade and Development (UNCTAD)’s earlier study on economic diversification in LLDCs reveals that they are distinguished from the other developing countries by their dominant resource-based activities, where all but three10 LLDCs exported primarily resource-based products.11 Moreover, the evolution of the share of resource-based activities over the past decade suggests that LLDCs as a group have become increasingly commodity-dependent, where weak private sector, fragmented policies and institutions, and underdeveloped productive capacities have failed to transform endowments into comparative advantages.12

In sum, despite high natural resource endowments, LLDCs suffer from structural rigidity that constrain their growth and development prospects and hinder their participation in high-end supply and value chains. The expectation that the advent of RVCs and GVCs opens opportunities for resource-based economies to attract FDI has not fully materialized for LLDCs. In fact, despite FDI flows being historically concentrated in their extractive sectors, there is little economic complexity or deeper production transformation observed in their economies (Figure 2). Thus, in the decades ahead, LLDCs need to prioritize capturing the rents from natural resources in production transformation by addressing gaps in their productive capacities, especially in fostering human capital, infrastructure (including electricity and ICT), developing dynamic and vibrant private sector, and functioning institutions.

The geographic dispersion of production renders supply and value chains susceptible to internal or external shocks. The global financial and economic fallout of 2007-09, the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, domestic conflicts, and recurring climate change tend to disrupt supply and value chains with devastating socioeconomic consequences.

Likewise, the simmering trade wars between major economic powers and the abruptly changing global trading regimes will have dire consequences for LLDCs. The unilateral imposition of tariffs by the United States and reciprocal tariff exchanges among major economic powers will no doubt disrupt supply and value chains worldwide, particularly in LLDCs.

Furthermore, pilot studies on the potential impact of the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) show that if implemented in 2026, the EUDR may have a significant impact on producers and exporters of agricultural products, particularly coffee, soybeans, sesame, forest products (wood), cocoa and palm oil, among others. Similarly, the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM)14 could potentially harm trade and development prospects of structurally weak and vulnerable economies, including LLDCs.

Moreover, supply and value chains are highly complex, requiring specialized knowledge, technology, and skills-driven engagements and management. For instance, supply networks must be carefully managed to improve quality, reduce costs, and lead time. This calls for monitoring the inbound, outbound, and procurement functions within the supply chains, as well as the nodes and linkages around the world, with an up-to-date information system.15 16

Way Forward

Although it is difficult to foretell the direction and policy implications of the currently fractured multilateralism, UNLDC-III needs to take bold but realistic actions and adopt implementable measures, supporting LLDCs. In this regard, it is important that: (a) LLDCs conduct soul-searching reflection on the lessons from the recent global changes, especially the sudden disruption of preferential market access and reduction in development aid; and (b) their trade and development partners pursue policies that are conducive to the development of these countries. Global partnership (including in the context of South-South cooperation) can also assist in facilitating LLDCs’ integration into RVCs and GVCs by fostering developmental regionalism and building regional infrastructure as a public good.

While LLDCs are not homogeneous, the building of productive capacities, capital accumulation, and technological catch-up are key to enabling them to develop critical domestic supply chains and effectively participate in RVCs and GVCs. This entails strengthened partnerships and calls for gearing domestic macroeconomic, industrial, trade, rural, infrastructure, and other sectoral policies toward employment generation, poverty reduction, and unleash the potential of natural resources. For instance, along with limiting domestic currency appreciation, governments of LLDCs can apply countercyclical spending patterns (i.e., saving during high commodity prices and spending/investing during fiscal and liquidity crunches).

LLDCs must also foster well-functioning institutions while ensuring coherence between various policies and positioning domestic firms in supply and value chains. Supporting domestic firms should target dynamic, labour-intensive, export-oriented, and value-adding firms, rather than solely focusing on the attraction of foreign firms that do little to add value or transfer skills and technology to the domestic economy.

Looking ahead, UN-LLDC III is a critical milestone both for LLDCs and the international community to catalyze concrete action and innovative approaches to sustainable trade and development. The opportunity must not be lost to stand alongside LLDCs as they seek forward-looking approaches to boost their own domestic productive capacities and forge global partnerships to support more sustainable, just and inclusive futures.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Editors Note: This article was originally published in Trade Insight Vol. 21, No. 1-2, 2025.

This article is prepared in full consideration of ST/AI/2000/13 section 2, and it is in the personal capacity of the author. Therefore, the opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect or represent the official views of UNCTAD or the UnitedNations.

References

- The concept of productive capacities was developed by the UNCTAD in 2006 and is broadly defined as the productive resources, entrepreneurial capabilities and production linkages that together determine a country’s ability to produce goods and services that will help it grow and develop. ↩︎

- There is no single unified conceptual definition to distinguish between supply and value chains. In this article the definition provided by Dubey, S. et al (2020), which articulates a supply chain as “the chain of suppliers making inputs or raw material to a final product” and a value chain as “functional activities through which the value created by the chain” is adopted or implied. ↩︎

- The current list of LLDCs includes Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Botswana, Bolivia, Bhutan, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Central African Republic, Chad, Ethiopia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Lao PDR, Lesotho, Macedonia, Malawi, Mali, Moldova, Mongolia, Nepal, Niger, Paraguay, Rwanda, South Sudan, Swaziland, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uganda, Uzbekistan, Zambia and Zimbabwe. ↩︎

- UNCTAD. 2019. Commodities and Development Report 2019: The State of Commodity Dependence 2019. New York and Geneva: United Nations. ↩︎

- UNCTAD. 2020. Productive Capacities Index: Focus on Landlocked Developing Countries. Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- UNCTAD. 2020. Building and Utilizing Productive Capacities in Africa, and the Least Developed Countries: A Holistic and Practical guide. Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. ↩︎

- The Productive Capacities Index (PCI) is composed of 42 indicators among eight categories: Natural Capital, Human Capital, Energy (electricity), Information & Communication Technology (ICT), Private Sector, Structural Change, Transport and Institutions (for more details on the PCI, including the statistical methodology, database and related resources, visit http://pci.unctad.org). ↩︎

- Collier, Paul. 2007. The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries Are Failing and What Can Be Done About It. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ↩︎

- These are Lesotho, which registered some low-technology manufacturing, Nepal (low-technology manufacturing) and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (mid-level manufacturing). While this can be seen as a positive trend, these LLDCs themselves are locked in low value-added manufacturing exports. ↩︎

- ibid. Note 5. ↩︎

- Delelegn, Mussie and T. Tesfachew. 2025. “Fostering Productive Capacities and Structural Transformation in Africa: The Role of the Private Sector.” Book Chapter, forthcoming. ↩︎

- Note: For indicators and data sources used to measure structural change and economic complexity, see http://pci.unctad.org. ↩︎

- EU Regulation 2023/956 introduced CBAM with the objective to reduce carbon emissions, put a “fair price” on the carbon emitted during the production of carbon-intensive goods imported into the EU, and encourage “a cleaner industrial production”. ↩︎

- ibid. Note 5. ↩︎

- ibid. Note 7. ↩︎